Introduction

Sir Antony Hoare[1] introduced the concept of Null-references or a Null pointer[2] back in 1965 with the release of ALGOL W. In 2009 he spoke about it as his “Billion Dollar Mistake”[3]. Dereferencing a Null pointer will address an invalid memory region, usually leading to runtime errors or complete crashes. Despite many efforts, this is still a thing in 2025.

In Java, there are no pointers in the sense of C. However, all non-primitive variables are object references and these can be null. Accessing an uninitialized variable or a variable with the value null results in the infamous NullPointerException. As of 2025, there are only mere wishes to have Null-restricted and nullable types in the Java language itself, hence people are still looking for a solution they can have now.

A brief history about @NonNull-standards

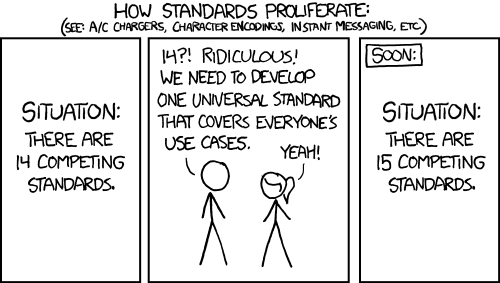

Obviously, there’s a xkcd comic by Randall Munroe that says it all:

The first milestone release of JSpecify appeared in 2020. By then, it was preceded by

- JSR 305: Annotations for Software Defect Detection[5] from 2006, never published as JSR, available as part of SpotBugs (originally FindBugs)

org.jetbrains.annotations.NotNull: JetBrains specific annotations for static code analysisorg.eclipse.jdt.annotation. NonNull: Eclipse compiler-specific annotations for static code analysis@NonNullfrom Project Lombok[6], not intended as a verification tool, but rather an instruction to add null checks to the bytecodejavax.valiation.constraints, more of a tool for validating input values

JSpecify

The above list is not even complete, so why another standard, and what makes JSpecify special? First of all, JSpecify was defined and designed by a committee, similar to Java Specification Requests (JSR). JSRs are usually led by experts from industry and research. JSpecify is led by, among others

- JetBrains

- Meta

- Microsoft

- Oracle

- Sonar

- Uber and

- Broadcom (Spring Framework)

The range of companies involved demonstrates their shared interest and goal: to provide a new set of annotations with precise semantics regarding nullability and usage that several heavyweights in the industry were able to agree on.

“Nullness”

We need to first understand the concept of “Nullness” to be able to use JSpecify effective. A type like String that isn’t annotated with either @Nullable or @NonNull means what it always used to mean: its values might be intended to include null or might not, depending on whatever documentation you can find. JSpecify calls this “unspecified nullness”. By using JSpecify annotations, you can express that

- a type maybe

null - a type cannot be

null - type variables maybe

nullor cannot benull(i.e. elements of aList<T>)

JSpecify consists of four annotations

- two for usage on types,

@Nullableand@NonNull - two for scope usage,

@NullMarkedund@NullUnmarked

The latter mark a package or a complete Java-module either as null-safe, that is all parameters are assumed to @NonNull, so that each parameter that might be null, must be annotated with @Nullable. The usage of @NonNull in that scope is superfluous. @NullUnmarked expresses the opposite and reverses the effect of @NullMarked. This is helpful to migrate individual packages of a module step by step.

@Nullable and @NonNull aren’t applied to local variables, they should be applied to type arguments and array components. The reason is that it is possible to infer whether a variable can be null based on the values that are assigned to the variable when everything else is null-checked.

Hierarchical, or not? Java-Packages and Modules

Java packages are not hierarchical. The two packages

a.banda.b.cdo not have a “c is part of b” relationship, even though many tools represent or evaluate it differently. Java modules, on the other hand, have a hierarchical relationship with packages: packages are subelements of a module. Therefore,@NullMarkedcan be applied semantically correctly at the Java module level and@NullUnmarkedcan be applied as needed at the package level. At the package level alone, both annotations only make sense with a checker framework that views packages as hierarchical constructs and ensures behavior similar to that of Java’s module system.

Dependencies and compromises

JSpecify is located under the coordinates org.jspecify:jspecify:1.0.0, and the module has no further dependencies. However, the annotations are available not only during compilation but also at runtime (@Retention(RUNTIME)), so the authors advise against using them in the provided or optional scope. This naturally has consequences for use in libraries: JSpecify becomes a transitive dependency. Anyone who, like me, has cursed more than once about incompatible versions of frequently used dependencies (commons-*, guava, older JSR-305 annotations, Jackson, to name a few) is skeptical at first. As the author of several smaller libraries, I don’t necessarily want to create more downstream ballast and am very cautious about using third-party APIs in my API.

Personally, I would draw the following line for libraries: If a library is only a small component of a larger framework and is not usually affected by the actual application code, I would refrain from using JSpecify. If the library is exposed and developers access interfaces directly, we will find good arguments to make JSpecify part of your API. Current IDEs will recognize these annotations and directly draw attention to possible problems with null values, without any further tooling

Going from unspecified Nullness to a defined setting

The first step of using JSpecify will be getting into a defined state. In my example project, which you find on Codeberg.org under /michael-simons/writing/src/branch/main/demos/jspecify[7], I chose a single package-info.java, to mark the whole project, which consists of a single package, as @NullMarked:

@NullMarked package ac.simons.javaspektrum.jspecify; import org.jspecify.annotations.NullMarked; |

Now all parameters are considered non-null by default. The following example shows a calculator that adds integer values. The first parameter must not be null, but what about the other summands? The example shows how nullness can be described precisely with JSpecify: @Nullable Integer @Nullable ... others means that the vargs argument others itself may be null, as well as any individual element of it:

package ac.simons.javaspektrum.jspecify; import java.util.Objects; import org.jspecify.annotations.Nullable; public final class Calculator { public Integer sum(Integer summand, @Nullable Integer @Nullable ... others) { int sum = Objects.requireNonNull(summand, "One summand is required"); if (others != null) { for (var other : others) { sum += Objects.requireNonNullElse(other, 0); } } return sum; } } |

The JSpecify manual covers the annotation of types, type parameters, and generics in detail in the section Generics[8]. Together with the brief excursions into type theory, I find this section outstanding and believe that it cannot be improved upon without making the concept a genuine part of the language, as described in the as-yet-unnumbered JEP “Null-Restricted and Nullable Types”[9]. It is striking here that both JSpecify and the Java architects use the same theoretical background: @Nullable String and String? are different types than @NonNull String and String!. The former are union types of null and String, the latter are not.

Back to the example. All the following calls are valid:

var calc = new Calculator(); calc.sum(1); calc.sum(1, 2, null, 3); calc.sum(1, ((Integer[]) null)); |

While IntelliJ and other IDEs will complain about calc.sum(null); that we are using literal null with a @NonNull parameter, but still happily compile and run the following test successfully:

package ac.simons.javaspektrum.jspecify; import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test; import static org.assertj.core.api.Assertions.*; class CalculatorTests { @Test void shouldRequireOneSummand() { var calc = new Calculator(); assertThatNullPointerException() .isThrownBy(() -> calc.sum(null)) .withMessage("One summand is required"); } @Test void shouldNotFailOnBadUsage() { var calc = new Calculator(); assertThatNoException().isThrownBy(() -> calc.sum(1, (Integer[]) null)); } } |

JSpecify alone is only a tool. Annotations are used to replicate a feature that should be part of the language. Without static analysis, i.e., another tool in the build process, the annotations remain just some arbitrary metadata for the Java compiler. Hopefully, this explains something that the attentive reader might already have spotted: The Calculator class uses Objects.requireNonNull to check the parameter summand, which is actually declared as @NonNull, and also tests whether the varg parameter others is not null as a whole and finally also whether there is a null value inside that others array.

Null, away!

Of course, there is not just one solution to this problem, but several: a nullness analyzer based on annotations that recognizes JSpecify annotations. One of these is uber/NullAway[10]. NullAway is an Error Prone[11] plugin. Error Prone itself augments the type analysis of the Java compiler so that it can detect more errors.

Error Prone itself is a great tool, but since it intervenes deeply in the Java compiler process, it requires several packages from the jdk.compiler module that are not usually exported in modern Java versions. The following listing shows the necessary exports for Java 25:

--add-exports jdk.compiler/com.sun.tools.javac.api=ALL-UNNAMED

--add-exports jdk.compiler/com.sun.tools.javac.comp=ALL-UNNAMED

--add-exports jdk.compiler/com.sun.tools.javac.code=ALL-UNNAMED

--add-exports jdk.compiler/com.sun.tools.javac.main=ALL-UNNAMED

--add-exports jdk.compiler/com.sun.tools.javac.parser=ALL-UNNAMED

--add-exports jdk.compiler/com.sun.tools.javac.processing=ALL-UNNAMED

--add-exports jdk.compiler/com.sun.tools.javac.tree=ALL-UNNAMED

--add-exports jdk.compiler/com.sun.tools.javac.util=ALL-UNNAMEDAfterward, you can configure Error Prone together with NullAway as a Compiler-Plugin in your build-process. The following listing demonstrates how that is done with Maven:

<build> <plugins> <plugin> <groupId>org.apache.maven.plugins</groupId> <artifactId>maven-compiler-plugin</artifactId> <configuration combine.self="append"> <compilerArgs> <arg>-XDcompilePolicy=simple</arg> <arg>--should-stop=ifError=FLOW</arg> <arg>-Xplugin:ErrorProne -Xep:NullAway:ERROR -XepOpt:NullAway:OnlyNullMarked=true</arg> </compilerArgs> <annotationProcessorPaths> <path> <groupId>com.google.errorprone</groupId> <artifactId>error_prone_core</artifactId> <version>2.38.0</version> </path> <path> <groupId>com.uber.nullaway</groupId> <artifactId>nullaway</artifactId> <version>0.12.9</version> </path> </annotationProcessorPaths> </configuration> </plugin> </plugins> </build> |

The steps for Gradle are similar and documented right on the NullAway GitHub-Project. The important parameters here are -Xep:NullAway:ERROR -XepOpt:NullAway:OnlyNullMarked=true: All null related issues should turn into actual compile errors, but only for Modules and Packages that are NullMarked. The example project comes with a profile that uses this configuration which can be activated like this: mvn clean verify -DwithNullaway. In doing so, the test won’t compile anymore:

Compilation failure

[ERROR] /jspecify/src/test/java/ac/simons/javaspektrum/jspecify/CalculatorTests.java: [13,76] [NullAway] passing

@Nullable parameter 'null' where @NonNull is required

[ERROR] (see http://t.uber.com/nullaway )If our library now could assume always being used with a Null-checker, we could get rid of our own null checks.

What about other languages?

Kotlin has nullable and non-null types, and by default, all values are non-null. Without JSpecify annotations in Calculator, this Kotlin test is valid code:

package ac.simons.javaspektrum.jspecify

import kotlin.test.Test

import kotlin.test.assertEquals

class KalkulatorTests {

@Test

fun sumShouldWork() {

val a: Int? = 1

val b: Int? = null

assertEquals(2, Calculator().sum(a, b, 1)) }

} |

Since Calculator is a Java class, all parameters are nullable without further information from the Kotlin compiler’s perspective, so the correct type is Int?. However, once the package is marked as @NullMarked, the above test no longer compiles—without any further configuration or plugins:

Kotlin: Argument type mismatch: actual type is 'Int?', but 'Int' was expected.This is because the Kotlin compiler, since version 2.1.0, treats Java code annotated with JSpecify as null-safe types. As a result, introducing JSpecify annotations into a code base is a breaking change that requires not only a minor, but a major version bump. The correct call now is this:

Calculator().sum(a!!, b, 1)Alternatively, a can be declared Int.

Conclusion

JSpecify is exceptionally well documented and specified, and is a fine example of how committee-organized standards can produce good results, especially when more than just one or two groups are represented.

In my current role, I have mixed feelings about JSpecify. It does exactly what it’s supposed to do—especially in conjunction with NullAway—but only then. As a library developer, I can’t do without null checks. Whether I use Objects.requireNonNull and indirectly throw a NullPointerException or prefer IllegalArgumentException is another discussion. If I wanted to annoy the world, I would probably throw @lombok.NonNull at it, as this annotation generates the above checks in the bytecode for me.

From an application perspective, the situation is different, and I would recommend JSpecify and NullAway without reservation:

- Frameworks such as Spring and Jackson will use JSpecify in their upcoming major versions (which, incidentally, was my first encounter with JSpecify; I am responsible for Spring Data Neo4j), and application developers can now easily check whether frameworks are parameterized correctly

- Application code benefits directly from the annotations, and application developers can usually dispense with further null checks if tools such as NullAway are used at the CI level

Links

| 1 | Sir Antony Hoare | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Hoare |

| 2 | Null pointer | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Null_pointer |

| 3 | “Billion Dollar Mistake” | https://www.infoq.com/presentations/Null-References-The-Billion-Dollar-Mistake-Tony-Hoare/ |

| 4 | xkcd.com/927 | https://xkcd.com/927 |

| 5 | JSR 305: Annotations for Software Defect Detection | https://jcp.org/en/jsr/detail?id=305 |

| 6 | Project Lombok | https://projectlombok.org/features/NonNull |

| 7 | /michael-simons/writing/src/branch/main/demos/jspecify | https://codeberg.org/michael-simons/writing/src/branch/main/demos/jspecify |

| 8 | Generics | https://jspecify.dev/docs/user-guide/#generics |

| 9 | “Null-Restricted and Nullable Types” | https://openjdk.org/jeps/8303099 |

| 10 | uber/NullAway | https://github.com/uber/NullAway |

| 11 | Error Prone | https://errorprone.info |

No comments yet

Post a Comment